Understanding Strength Adaptation

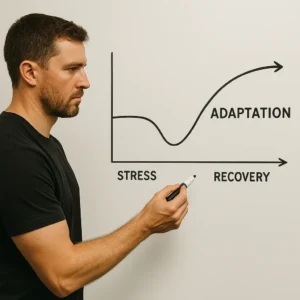

Strength is the body’s remarkable ability to respond to challenge. When you lift weights, sprint, or perform bodyweight exercises, you’re doing more than just moving you’re sending a signal to your body that it needs to adapt.

At its core, strength adaptation is a process of biological remodeling. Each repetition, each session, creates tiny amounts of muscle damage (microtrauma). Your body interprets that damage as a reason to rebuild stronger, more resilient, and better prepared for next time.

“Performance isn’t an accident it’s the product of precision, patience, and purpose.”

— Chris Dear, CD Performance

The Role of Progressive Overload

The foundation of any effective training program is progressive overload the gradual increase in stress placed upon the body during exercise. This can be achieved through more weight, more reps, more sets, or reduced rest time.

Without progression, adaptation slows down. Your body only grows stronger when it’s given a reason to. Think of it like this: if you keep lifting the same weight week after week, your body stops needing to change.

A well-designed program includes small, consistent increases enough to stimulate growth without tipping into overtraining. In practice, that might mean adding 2.5kg to your lifts every couple of weeks, or an extra set on your main compound movements every training cycle.

For a deeper understanding of programming fundamentals, check out Coach Grimmy’s philosophy on functional training over on RB100.Fitness.

Neurological Adaptation: Strength Beyond Muscle

In the early stages of training, most strength gains aren’t from bigger muscles — they’re from a smarter nervous system. This process, called neurological adaptation, involves your brain and nerves learning how to fire muscles more efficiently.

Essentially, your central nervous system (CNS) becomes better at recruiting muscle fibers, improving synchronization, and increasing firing rate. This explains why beginners often get stronger quickly without visible size increases.

Over time, as technique improves and the nervous system becomes more efficient, the body starts to layer on muscle hypertrophy — increased muscle size — leading to even greater strength potential.

Hypertrophy and Structural Change

Once the neurological improvements plateau, hypertrophy becomes the next key stage of adaptation. This is the increase in the cross-sectional area of muscle fibers. It’s driven primarily by mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and muscle damage.

When managed correctly, hypertrophy isn’t just about aesthetics — it’s about increasing your body’s capacity to generate force. The stronger the muscle fibers, the more potential for performance.

For endurance athletes or CrossFitters, balancing hypertrophy with endurance becomes a strategic challenge — too much bulk can hinder speed, but too little strength can limit power output. That’s why strength training for performance is always a balance of art and science.

Recovery: The Unsung Hero of Strength

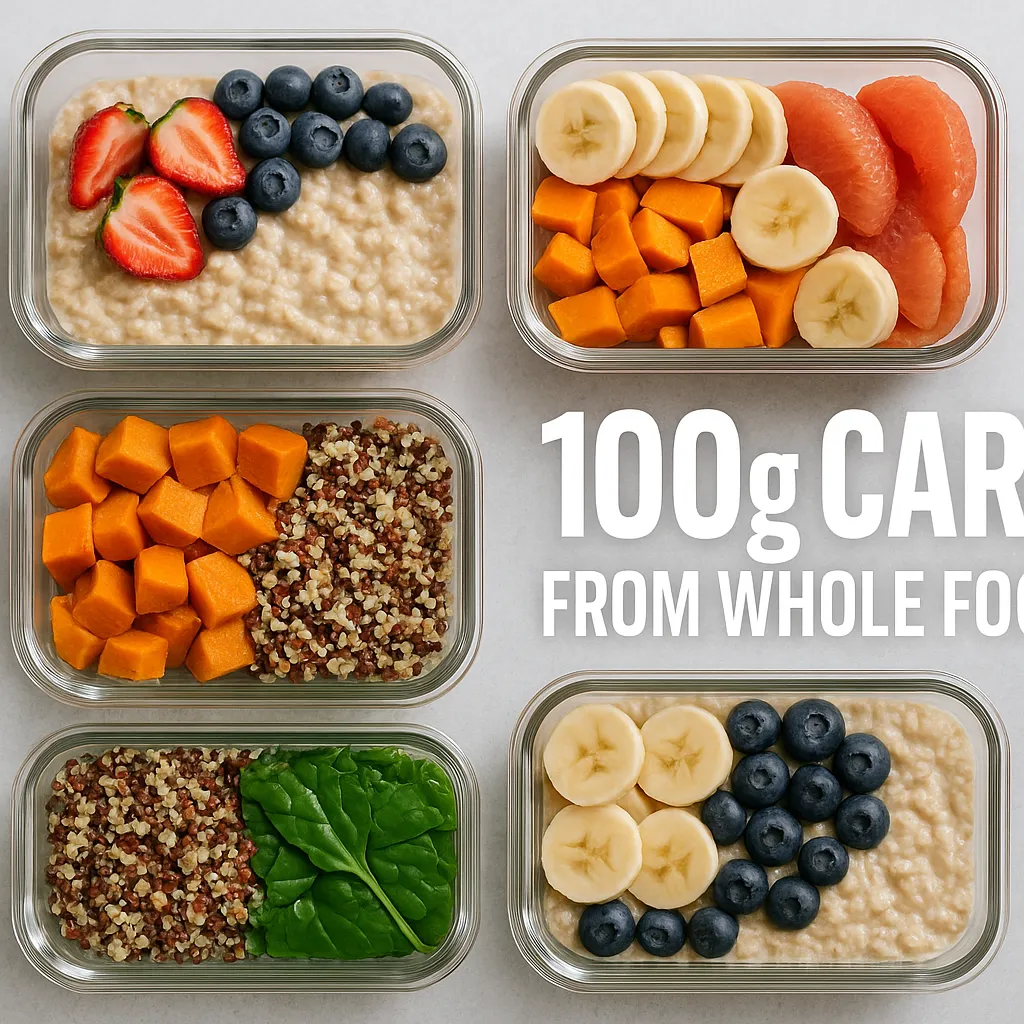

Adaptation doesn’t happen in the gym — it happens in recovery. Training provides the stimulus, but sleep, nutrition, and rest provide the environment for growth.

After an intense training session, muscle protein synthesis (MPS) ramps up, but it can only continue efficiently with sufficient amino acids (from protein) and energy intake (from carbohydrates and fats).

Lack of recovery doesn’t just slow progress — it reverses it. Without adequate sleep and nutrition, cortisol levels remain high, muscle repair is blunted, and nervous system fatigue accumulates.

“Train hard, recover harder. The body can only adapt if it’s given the space to do so.” — Chris Dear, CD Performance

To optimise your recovery habits, read more in RB100.Fitness’s guide to Nutrition & Recovery.

The Science in Practice

For coaches and athletes alike, understanding the mechanisms of adaptation allows for smarter programming. Whether it’s periodisation, auto-regulation, or deload weeks, each tool serves to manage the stress–recovery–adaptation cycle effectively.

An elite athlete might train six days a week, but the principle is the same as for a beginner training three — stimulus, recovery, adaptation.

If you’re serious about improving your strength, track your progress. Data doesn’t lie. Note your loads, sets, reps, and rate of perceived exertion (RPE). Over time, these records become a roadmap for intelligent progression.

(See more on tracking tools and performance metrics in RB100.Fitness’s Habits, Tech & Mindset section).

Final Thoughts

The science of strength adaptation reveals a simple truth: your body is always adapting to what you demand of it. Train with intention, recover with purpose, and trust the process.

Whether your goal is to lift heavier, run faster, or move better, the same biological principles apply. Consistency, progressive overload, and recovery form the unbreakable triad of progress.

As a coach and athlete, I’ve seen this process work time and again — from recreational lifters to world-class performers. You can’t cheat biology, but you can learn to work with it.

So the next time you’re under the bar, remember: every rep is communication with your body. Make sure it’s sending the right message.